By Tom House, PhD, with Lindsay Berra

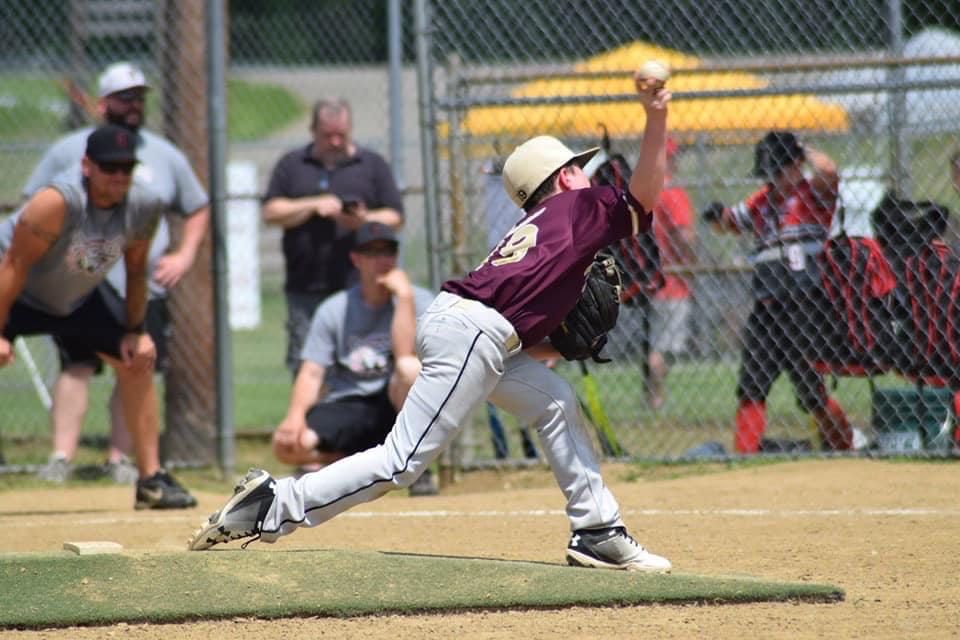

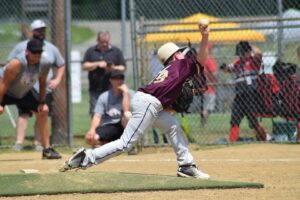

In today’s game, a lot of pitching coaches believe left handers should throw from the left side of the rubber and right handers should throw from the right side of the rubber, but this just isn’t always the case. You want to throw from the rubber at the position from which your body finishes from the middle of the rubber to the middle of home plate. That’s how you know your mechanics are where they should be. Your back foot will literally create a line in the dirt – we call that a pitcher’s drag line – that will clearly show whether or not your body is where it should be.

Try this. In the bullpen, draw a two or three-foot line in the dirt from from the middle of the rubber toward the center of home plate. Then, throw a few pitches and have a look at your drag line to see where your toe is finishing. If you’re a right-handed pitcher and your drag line is six inches to the third base side of the center line, move six inches toward first base. If you’re a lefty and your drag line is four inches to the first base side of the center line, move four inches toward third base. You need to move your body on the rubber until your drag line finishes on that center line, and that will be the most efficient position for your body. You want all your energy to run straight down Broadway, on the shortest path from the middle of the rubber to the middle of home plate, and you want your drag line, your belly button, your spine and your nose all on that line.

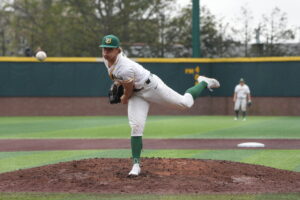

You stride the way you were born to stride. Our Mustard database includes over 900 big-league pitchers on whom I have done motion capture analyses since 1986. Of those pitchers, 60% stride slightly closed, or across their bodies; think Kenny Rogers. 20% open up, like Mike Mussina. And 20% are directly to home plate, like Greg Maddux and Nolan Ryan. But how you stride doesn’t matter; that’s unique to you. What’s important is how far you stride and how you line that stride up with your momentum going from the middle of the rubber to the middle of home plate.

Keep that back foot down. All good pitchers, especially hard throwers, have their back foot on the ground until the ball leaves their hand. That’s how they keep their energy going in the right direction. Keeping the back foot down allows the low back to go from hyperextension into flexion and create a whip. If it comes off the ground too soon, it’s an indicator that your head is getting in front of you center of gravity, or in front of the belly button, too soon. If you watch video of Nolan Ryan pitching, his back foot stayed on the ground until the ball was almost four feet out of his hand. He used to tell me, “Tom, I want to ride the ball. I want to stay behind the ball as long as I can.”

Your drag line should be the length of two of your feet. That’s not two feet or 24 inches, but two of your size 9s or size 13s. If it’s shorter, your head is getting ahead of your belly button. Your head needs to stay over or behind your center of mass as you stack and track to throw the ball, and if it doesn’t, your foot will lift off the ground too soon. You cannot stack and track if your back foot is off the ground. So, if you’re wearing out the toe of your cleat, you’re doing something right. And remember, there is no perfect drag line. Some are curvy, some are straight, some make a shape like a hook. As long as all those imperfect movements take place inside the body, and finish on the center line, the vectors are good.

Your drag line is like a rudder on a boat. It controls the direction of energy, keeps all your vectors going toward your target and reflects what your head is doing into ball release. If there is no rudder on the back of the boat, the front goes wherever it wants to go, or along the path of least resistance. But as a pitcher, you have a very set path, from the middle of the rubber to the middle of home plate. Your back foot is your rudder, and can be used as a director or a redirector, and you can use it to help your head position. For example, if a right-hander’s head is too far toward third base, you can tell him to create a drag line like a bowler, with the back foot going behind him as he throws the ball. It will guarantee his head stays on line. Most pitchers who step closed, or across their body, will benefit from a bowler’s drag line.

Having a drag line will not negatively affect velocity. People ask me this all the time, but think about the science and the way energy is created in a pitching motion. By the time your landing leg hits the ground at the end of your stride, you have transferred your weight and all the energy is going to your arm and the baseball. Having your foot on the ground when that transfer of energy takes place does not steal your velocity. Rather, it can enhance it, because it keeps all your vectors going in the right direction and it’s a second source for torque; you can generate more energy when you are pushing with both feet on the ground.

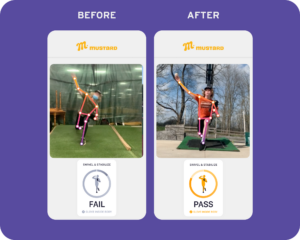

Drag line can be predictive of health. Where your drag line is at release is an indication of where your center of mass is at release. If it’s way to one side, your body has to work harder to get back to its target. When you’re not working efficiently, your inefficiencies become stresses that can lead to injury. Dean Taylor, my colleague at the National Pitching Association, has done amazing research into injury rates to big-league pitchers as they relate to drag line. He watched video of all 624 pitchers rostered in the big leagues in 2019. 71% of those who ended up on the Injured List with shoulder injuries had misdirected, short or nonexistent drag lines. That number jumped to 75% for pitchers with elbow and oblique injuries. That means you are 2.5 times more likely to injure your shoulder and 3 times more likely to injure your elbow or oblique if your drag line isn’t what it should be.

If you’d like more great content from Mustard, and you’d like to evaluate and improve your own pitching mechanics, download the Mustard pitching app today.