By Tom House, PhD, with Lindsay Berra

In June of 2010, I watched, along with the rest of the sports world, as American John Isner and Frenchman Nicolas Mahut played the longest tennis match in history. It was at Wimbledon. It took 11 hours and five minutes over the course of three days, and went on for a total of 183 games. At eight hours and 11 minutes, the final set alone was longer than the previous longest match, and the whole thing got me thinking: How come tennis players can swing a racquet literally thousands of times and have no issues with their arms?

The answer isn’t that complicated. While the overhead serve is very similar to the pitching motion, there is one key difference. Tennis players hang onto the racquet through the whole range of motion, which strengthens the decelerator muscles. A pitcher lets the ball go, forcing his arm to decelerate without the implement, with the added force of going down the mound. This is why the back of the pitcher’s shoulder is always in jeopardy; in general, too many pitchers train the accelerators, and neglect the decelerators.

THE HISTORY OF WEIGHTED BALLS

Though that Isner-Mahut match got me thinking about decelerator muscles, it certainly wasn’t the first time I’d thought about training with weighted balls. If you watch tape of old Yankees games, you’ll see Mariano Rivera loosening up in the bullpen and also staying loose between innings by doing exercises with a lead ball. Glenn Mickens invented that; Mickens pitched in a few games for the Dodgers in the 1950s and went on to coach baseball at UCLA from 1965 to 1989.

In 1974, the year he appeared in a record 106 games for the Dodgers, pitcher Mike Marshall threw a 16-pound shotput every day for 20 minutes in the outfield. He was always in trouble with the grounds crew. And he also threw batting practice whether he was pitching or not. Dr. Mike has both a Masters and PhD, and he was the first to take weighted balls to the next level.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, I did a throwing study with Dr. Coop DeRenne, a kinesiology professor and baseball coach at the University of Hawaii. Our research, done over the course of one year with five high schools and five universities nationwide, showed you could improve velocity by over and under-loading. That was the first real research study done on weighted balls, and that’s when we came up with throwing 20 percent heavier and 20 percent lighter. We didn’t come up with a complete protocol, but we did publish a book based on the research, called “Implement Weight Training.” We had a product with Diamond Baseball called “The VIP Program” – a green 4-ounce ball and a black 6-ounce ball – that was eventually bought by Decker Sporting Goods.

It was later in my career, around 2008, that we started doing research at the University of Southern California on weighted balls and how they might fix GIRD, or glenohumeral rotation deficit. But in using weighted balls to treat gird, we realized the protocol also improved velocity. I presented that research at the American Sports Medicine Institute in Birmingham in 2011. But, if you think about it, kids playing pickup or sandlot baseball, throwing Wiffle balls (1 ounce), tennis balls (2 ounces), Pinky balls (3 ounces) or footballs (16 ounces) as hard as they can, have unwittingly been doing weighted ball training for years. This is not new!

THE MOUND CHANGES EVERYTHING

If you weigh 200 pounds, when you throw a baseball from your knees, your ground force production is 200 pounds, equal to your bodyweight. When you get on your feet and step and throw, your ground force production is 2X bodyweight, or 400 pounds. When you run-and-gun, or crow hop, or Happy Gilmore, or whatever else you’d like to call it, your ground force production is 4X bodyweight, or 800 pounds on flat ground. But when you throw off the pitcher’s mound, your ground force production increases to 6X bodyweight. We evolved running and throwing spears on flat ground to catch our dinner. We did not evolve throwing off the mound; it is the only unnatural thing about pitching, and therefore, 6X bodyweight is not in our genetics. This is why we don’t throw heavy balls off the mound. It’s just too much stress on all the throwing muscles, connective tissue and joints. It may improve velocity for a brief period, but you will eventually pay the price.

THE 3:2 RATIO

When we did the research, we realized three muscle groups accelerate the arm while only two muscles groups decelerate it. That 3:2 ratio seemed to hold up, especially when we started training the back side one-third more to balance it out. And to do that, we implemented “holds” into our weighted-ball program. That means, instead of throwing the weighted ball, the pitcher holds onto the ball through his entire motion. We do more holds than throws, because holds build strength and improve joint integrity while causing less joint separation and stress.

WINDOWS OF TRAINABILITY MUST BE ASSESSED

It doesn’t do preadolescents any good to throw anything much heavier than a baseball, because they’re not physically able to build strength yet. From the ages of 8 to 12, pitchers should train only with the 6-ounce, 5-ounce, 4-ounce and 2-ounce balls. When pitchers are around 13, right on the borderline, you can start them with the 1-pound ball to help them gain functional strength. But keep in mind, not all kids develop at the same rate, so they won’t all reach that window of trainability at the same time. If your 13-year-old can’t handle the 6-ounce ball, don’t move him to the 1-pound ball. In the beginning, they should do more holds than throws to build joint integrity, and once they can hang onto the 6-ounce ball at full speed in the rocker-leaper drill, you know they’re ready for more. If their mechanics are an issue, and you can fix mechanics neurologically, with any of our skill drills, with the towel drill being most efficient. But if they have issues with velocity or stiffness and soreness on the back side of shoulder, you have to remember they can only accelerate what they can decelerate. The 2-pound ball should only be added to the weighted-ball routine once a pitcher reaches adulthood, after the age of 18, to develop muscle mass.

ADAPTATION IS KEY

Many who criticize the use of weighted balls point to data collected solely on weighted ball throws, or to injuries that occur when pitchers go directly to throwing heavy balls from the run-and-gun, or on flat ground into a net, as hard as they can. The body just isn’t ready for it.

The research I did at USC was on the use of weighted ball holds and throws to correct GIRD, but the protocol we tested ended up also improving velocity and has been safely adapted into our training programs. However, following the program from the beginning is essential.

When you begin a weighted ball program, you start on your knees. You don’t get to graduate to step-and-throw on your feet until you can first handle three holds and two throws each of the 2-pound, 1-pound, 6-ounce, 5-ounce, 4-ounce and 2-ounce balls at max intensity with proper velocity spreads between the different weighted balls from that kneeling position.

When you adapt to max effort and intensity from the knees and you can hold on to all the different balls through the throwing motion at Mach 3 with your hair on fire, you know your decelerators are strong enough to handle your accelerators. Then, you can begin the same protocol of three holds and two throws with each ball from the step-and-throw or rocker position, and when you master that, only then can you move on to the run-and-gun. When you can complete the three holds and two throws with all the balls there, then you can measure the velocity spreads between the balls, assess whether the pitcher has a speed issue or a strength issue, and write a program accordingly. It should take six to eight weeks to get through the entire protocol. Arms get hurt when you don’t allow for proper adaptation and accommodation.

It’s also noteworthy that when you throw a standard, 5-ounce baseball from your knees on flat ground into a net as hard as you can, if everything is adapted functionally, the velocity you generate is 80% of what your ultimate velocity will be from a run-and-gun on flat ground, or from the stretch position in a bullpen session on the mound.

SOME LOOSE HOW-TOS; YOU’LL LEARN WHAT’S BEST FOR YOU

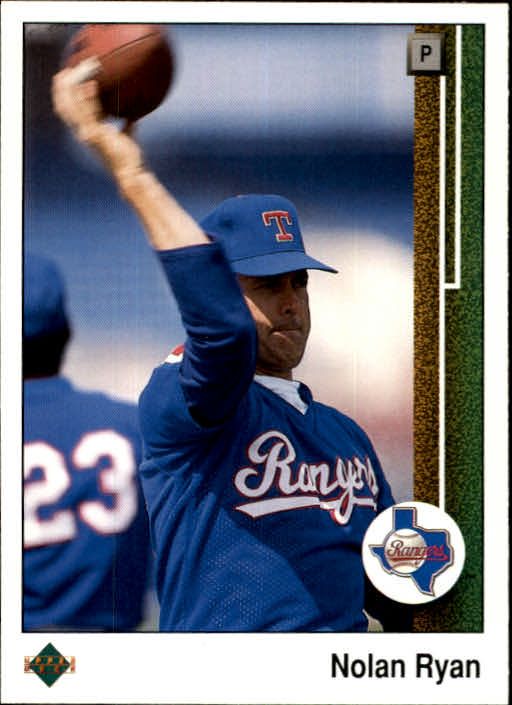

During the season, and around game performances, you should hold the heavy balls and throw the light balls. Over the course of a season, every pitcher loses strength. If you hold the heavy balls, from the knees, in the rocker drill, in Happy Gilmore, you will at least maintain strength. Then, in the offseason, you can do both. As far as when and how often you use the weighted balls, it really doesn’t matter. Some pitchers like them as a warmup; remember Rivera in the Yankees dugout, moving his arm around with that heavy, metal ball? Or Nolan Ryan throwing the football? A football weighs 16 ounces, so that’s certainly a weighted ball. Some pitchers need an hour to get loose, and some only need 20 minutes. Some feel great using weighted balls before they throw, and some like them as a recovery tool; holds are great the day after you pitch, again because you can go through the throwing motion without creating the stressful joint separation that throwing does.

HEAVIER AND LIGHTER BASEBALLS DO NOT EFFECT MECHANICS

If you are working with an implement that is heavier than your implement of skill – that is, anything heavier than a 5-ounce baseball – it’s for building strength. That’s the overload principle. Anything lighter than 5 ounces changes neuro-pathways and influences the nervous system to go faster. That’s the underload principle, and it is training speed. When we train with heavy and light, we are not as concerned about mechanics as we are about making the arm stronger and faster.

Our research indicates that when training muscles and patterning nerves, mechanics aren’t your ultimate goal. Until muscles and nerves can talk to each other, the skill at mechanical efficiency can’t happen. Kids who are 12 or under may have good mechanics or not, but there is no reason to worry, because in three weeks they’ll have totally different bodies. And depending on their windows of trainability, their biological age versus their chronological age will dictate whether to work on strength, speed or mechanics.

EXTERNAL ROTATION IS NOT PROBLEMATIC

Many coaches think weighted balls cause a detrimental increase in external shoulder rotation, but when the protocol is used properly, external rotation is only increased to a level of tolerance strength can handle. External rotation is a biomechanical inevitability. It is going to happen as the arm lays back, and it only becomes an issue if you don’t have the functional strength to stabilize the shoulder. Before you train with weighted balls, your coach should assess your functional strength and look at the velocity spreads between each ball to identify functional strength and weak links. At maximum intensity following our proprietary velocity spreads, if the pitcher can’t hang onto the ball, his or her decelerators are not yet strong enough to handle a weighted ball program, and he or she needs to do more training exercises to become functionally strong. If done properly, even a pre-adolescent person can use weighted balls. They’re just going to be using, at most, a six-ounce ball – just one ounce heavier than a baseball – for strength, and the four-ounce and two-ounce balls for speed. A young person would never throw a two-pound ball. The coach has to make the program personally adaptable for it to be safe and healthy.

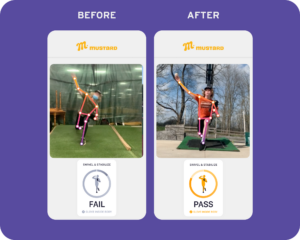

If you’d like more great content from Mustard, and you’d like to evaluate and improve your own pitching mechanics, download the Mustard pitching app today.