By Tom House, PhD, with Lindsay Berra

I had been a pitching coach for over 35 years when Cam Cameron, then the offensive coordinator for the San Diego Chargers, sent Drew Brees to see me. Initially, I was going to help Drew with the mental side of things, but because it’s what I do, we captured his motion also. And it turned out to be invaluable when he had to have shoulder surgery and was struggling with his mechanics after his rehab, because we were able to compare what he looked like throwing a football before and after surgery. At that time, I knew a lot about the throwing mechanics of baseball pitchers, but I had not yet applied that knowledge to quarterback mechanics. But, rotational athletes all have the same kinematic sequencing and the same mechanics, we just use different words to explain them. Once I learned how the numbers were changed by a larger and heavier implement – the football – we were off and running. Drew liked how his arm and his body felt, so he started telling his friends in the NFL, and they started coming to see me, too. And that gave me the opportunity to learn how quarterback mechanics are different from—and the same as—pitching mechanics. Here is some of what we figured out.

For Quarterbacks, Timing is Faster and Stride Length is Shorter

While pitchers have one full second to get into foot strike, quarterbacks have to transfer their weight and get into foot strike in under .2 seconds. And while a pitcher’s stride length is ideally the length of six to seven of his or her own feet, for a quarterback, that distance is just one of his or her feet. After foot strike, the ball should be released in under .45 seconds (faster for elite QBs), and follow through should occur within .7 seconds. By contrast, a pitcher should release the ball in around 1.25 seconds, and the full delivery should ideally take under two seconds. As my friend Adam Dedeaux from 3DQB explains it, while pitchers want to be as fast and long as they can, quarterbacks are trying to get the most out of their bodies in the least amount of space and the least amount of time. They have to be as small as they can be in the pocket because it’s crowded and everyone is coming after them.

A Quarterback’s Arm Path is Shorter Due to the Weight of the Football

The same arm action is utilized in quarterback mechanics and pitching mechanics, but because a football weighs three times as much as a baseball—15 ounces versus five—a quarterback’s arm path will be shorter. That is, the stroke—the distance the arm moves behind the athlete—won’t be as long, because the weight of the football will expose inefficiencies in quarterback mechanics if the arm action is long and loopy. However, the pattern of each individual’s arm path is unique to them, and takes care of itself if the eyes are level at release. Until the eyes are level, a thrower is not in his or her natural arm slot. Players will typically, without any information, do what’s naturally correct for them, whether their arm path is inside of 90 degrees, at 90 degrees or outside of 90 degrees. Players don’t typically get away from their natural arm slot unless they are given an incorrect teach. Keeping the eyes level also reinforces proper balance and posture; just as with a baseball, one inch of inappropriate head movement will cost two inches of distance at release point.

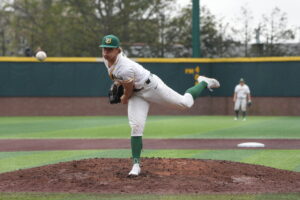

Quarterbacks and Pitchers Look Pretty Identical at Foot Strike

On paper, at foot strike, quarterback mechanics look the same as pitching mechanics; an athlete looks the same throwing a football as he or she does throwing a baseball. If you were to look at a 3D motion analysis of a pitcher and quarterback, once the front foot hits the ground, it will be identical. You can’t tell if they’re throwing a football or baseball. Whatever angles the athlete has for his or her opposite and equal position, it will be the same with both implements. Fast-forward to release, and pitchers and quarterbacks are similar here as well. Both release the ball eight to 12 inches in front of the landing leg big toe.

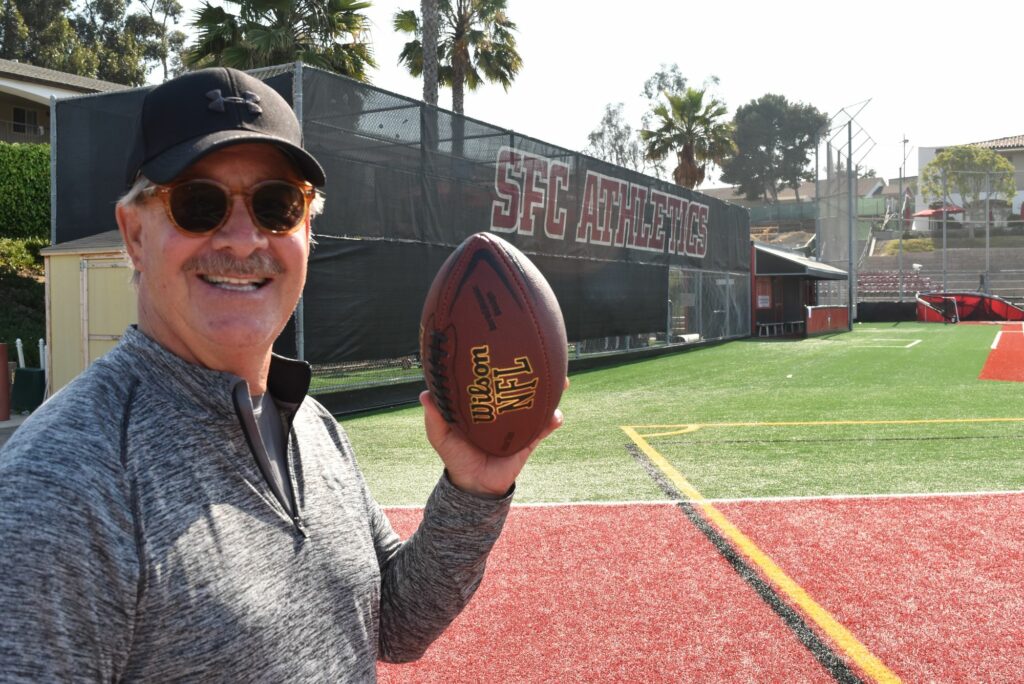

Coach Tom House working with NFL quarterback Mac Jones.

Coach Tom House working with NFL quarterback Mac Jones.Faster Timing and Shorter Stride Change the Dynamics of Power Generation

A quarterback with a shorter stride will not be able to generate the same foot pounds of energy as a pitcher with a longer stride. First, while elite pitchers get 40 to 60 degrees of hip and shoulder separation due to the length of their stride, a quarterback’s shorter stride will only allow 30 to 40 degrees of hip and shoulder separation, which means they store less torque in their throwing motions.

Additionally, when throwing on flat ground, an athlete can only generate four times their bodyweight in foot pounds of energy, while an athlete moving down a mound can generate six times bodyweight. Because quarterbacks don’t have the added benefit of the mound to enhance the production of ground force that moves up the kinetic chain, they primarily have to generate velocity with muscle. Because of this, a quarterback’s fitness program will be more geared toward the generation of velocity, while a pitcher’s fitness program should focus on strength and stabilization to handle the extra forces placed on the arm by the mound. Pitchers get hurt the most due to deceleration, whereas quarterbacks can usually still throw, even when they have shoulder issues, because there is not as much energy going through the system and the arm decelerates naturally when throwing a football.

Quarterbacks Must Find Their Own “Ankle Eye”

When we say “ankle eye,” we mean that if the inside of a thrower’s push-off ankle had an eye, it should be looking at the target. This is problematic for a pitcher, because his or her back foot must always be in contact with the rubber, which is fixed and influences the ankle eye to home plate. A quarterback has to move the back foot to find an ankle eye to where he or she is throwing the ball. Quarterbacks throw with their feet, and footwork for quarterbacks is critical. They have to step towards the target, with the back foot ankle eye perpendicular to the target line. The quicker their feet, the quicker their release. And if the ball doesn’t spiral properly, it’s usually a timing issue; go faster!

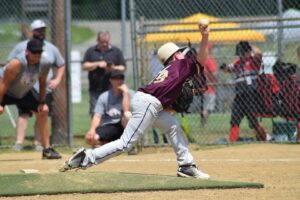

Quarterbacks and catchers throw in similar fashion.

Because catchers have to get rid of the ball as quickly as possible, their timing is more similar to a quarterback’s than a pitcher’s would be. The catcher throws with the shortest arm path on the baseball field, and, as with quarterback mechanics, footwork is critical. The catcher must pivot, establish an ankle eye to the target, and take a short, quick step in its direction to generate power. Catchers also have to stand up as they’re throwing, and if all their vectors are going in the right direction, this can help them generate power.

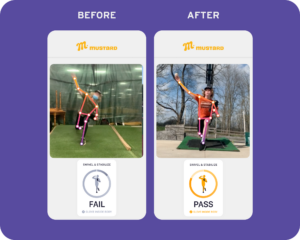

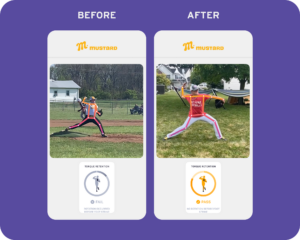

If you’d like more great content from Mustard, and you’d like to evaluate and improve your own pitching mechanics, download the Mustard pitching app today.